The Logical Trap I Saw and Peter MacKay Didn’t

A few days ago I wrote about the Conservative government’s new parole bill.

Under Bill C-56, the Statutory Release Reform Act, repeat violent offenders will only be eligible for parole six months prior to the end of their sentence.

There are some major problems with this sort of simplistic bill. Most concerning is that there is a danger limiting statutory release will actually increase risk to the community. This is particularly problematic given that the rate of violent re-offence for the offenders captured by the bill C-56 is very very low.

So, I was thinking a bit more about my criticism of bill C-56 and let’s cut to the chase – I committed the dreadful sin of employing a logical fallacy.

To be clear the weight of the evidence and expert opinion supports the conclusion that limiting parole for offenders, even violent offenders, increases the risk of re-offence. But I used a poor example to illustrate this:

Limiting the supervised release of these offenders is however a good way to increase the risk of violence. Again, take it from the Parole Board: When looking at the readmission rate for a violent offence, offenders released at warrant expiry (end of sentence) were ten times more likely to return to a federal institution because of a new violent offence than offenders who completed their sentences on full parole.

Can you see the problem?

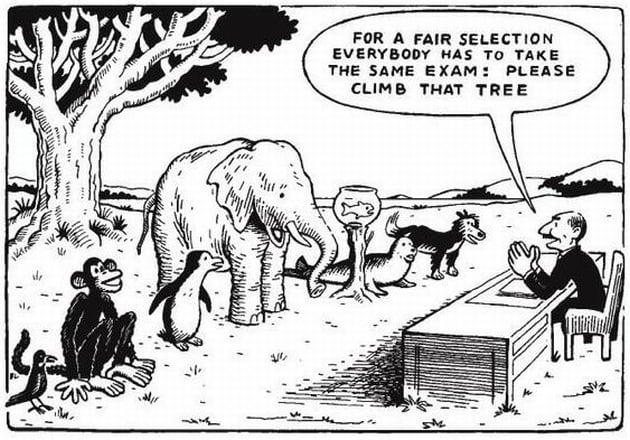

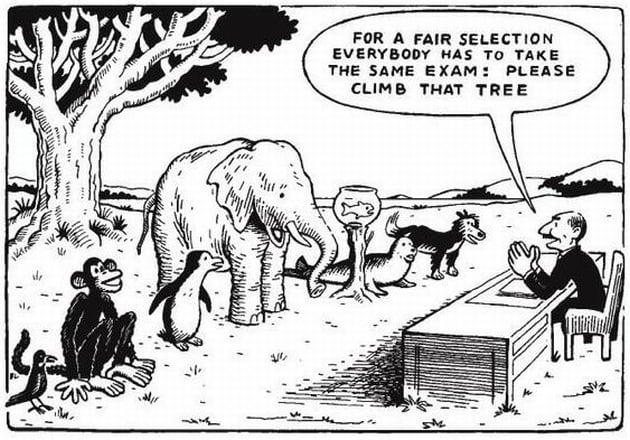

If only the most violent and least reformed offenders are held to the end of their sentences of course that group would have a higher recidivism rate.

It is simple selection bias.

I stand by the main point, as do the criminology experts, that a gradual and monitored reintegration is the best way to increase public safety. Bill C-56 runs contrary to this idea.

I also take some comfort that Peter MacKay fell into the same logical trap I did at the Sub-Committee on Corrections and Conditional Release Act:

Mr. Peter MacKay: With regard to statistics, I don’t want to get into all the nuances of what statistics may or may not represent, but one that does jump off the page at me concerns the revocation rate for breach of conditions, both full parole and statutory release.

For full parole, those who were revoked for breaching conditions—for instance, to stay away from playgrounds, stay off alcohol and drugs, and comply with reporting—it was 14.4%, and statutory release was 25.6%. So there was a 10% drop if the person was released on full parole.

For violent offenders, isn’t it a laudable goal to try to have a 10% drop in that revocation of breach? Because most times, at least for a violent offender, that revocation of breach may be something that’s going to lead to another violent offence.

I mean, if this statistic is correct—and I’m not saying it is—there’s a 10% drop here.

Commr Ole Ingstrup: No, I think it’s the other way, Mr. MacKay.

Mr. Peter MacKay: It’s 14.4%—

Commr Ole Ingstrup: For full parole. That means those who are under full parole will usually be the people who have slightly fewer conditions than the higher-risk people under statutory release. As well, they are more likely than the statutory people to abide by the rules. That’s really quite a natural thing.

Mr. Peter MacKay: My reading of this is that 25.6% of statutory releases were revoked.

Commr Ole Ingstrup: Yes.

Mr. Peter MacKay: If they were on full parole, only 14.4% were revoked.

Commr Ole Ingstrup: Yes, but that is exactly why they are in a different category; they represent a higher risk. Therefore, the two numbers are actually an indication that the system works relatively well in discriminating between who should go out on statutory release and who should go out on parole. The lighter cases and those who are more likely to behave the way they’re supposed to behave go out on full parole, as the system is supposed to work. Those who are more dicey will go out on statutory release later in the sentence.

Mr. Peter MacKay: I don’t read it that way at all. I see it as 10% more people on statutory release were revoked than people on full parole.

I guess the only difference between me and MacKay on this point is that I saw my error.

But given MacKay and the Conservative government’s pattern of introducing legislation that finds itself in directly contradiction to the evidence it seems that ignorance is indeed bliss.